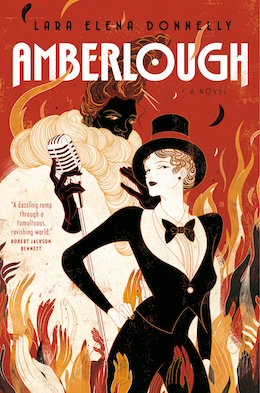

The One State Party is on the rise. Corruption and lawlessness have become too much for each of the Federated States of Gedda to handle on their own, and they’re looking for a great unifier in the midst of chaos. The seat of this chaos is Amberlough: a city awash in vice and beauty, where love is free and gender is questionable at best. To Amberlinians like Cordelia Lehane and Aristride Makricosta—performers at the Bumble Bee Cabaret—their world is untouchable by the likes of the One State Party (Ospies, for short). But when Ari’s lover, Cyril DePaul, gets in over his head while spying on the Ospies, they’re forced into a performance that may well cost their lives—or worse, their freedom.

I won’t be the last (and I’m certainly not the first) to call Lara Elena Donnelly’s Amberlough timely. Set amidst the lavish nightlife of a republic decaying into fascism, Amberlough is a piquant fruit of a book, ripening just in time for a year of protest and civil unrest. The novel is rich enough, luckily, for us to read its parallels and twists in a multitude of ways: it’s as much about sex as it is about art as it is about rebellion. It’s as much about our current age as it is the Weimar Republic as it is another world entirely. So you can read Amberlough as a queer Le Carré novel, or as a fantastical Cabaret—both descriptions are readily embraced by the publisher and the author—or you can read it as I read almost every book, regardless of intent: as a handbook for resistance. And Amberlough, with its lush prose and charmingly flawed characters, makes for an assortment of delightful tips.

Keynotes from Amberlough’s handbook on resisting a Totally Fictional Fascist Regime:

(This list is mostly spoiler-free! However, though the novel starts out slow, by the quarter-mark its pace is as fast and as devastating as its protagonists’ wits. Please direct any spoiler-y slip-ups to the Federal Office of Central Intelligence Services.)

1: Everything is the same but everything is different.

Amberlough is not a direct parallel—not to the historical past, nor to our political present. It’s a second world fantasy, with all the weirdness and malleability that comes with that territory; and it is anything (don’t let this list fool you) but didactic. Projects that are years, even decades in the making are taking on allegorical significance these days, regardless of the creators’ intent. So what, if art isn’t directly “about” politics, can it offer to the world of politics? It’s a question that scholars and artists have lost sleep over for centuries.

Amberlough is a fantastic example of how much both art and histories—and all those blurry-boundaried things in between—can provide for us, as well as all the things that they can’t. In times of trouble, after all, we turn to metaphor. Fiction can pack a heavier punch than reality when it needs to, just as allegory and figurative language can express emotion that plain language can’t grasp. The performances and provocations staged at Amberlough’s Bumble Bee Cabaret are therefore terribly important: in matters of self-expression and of gender and sexual liberation. They don’t save the day on their own, but they do make the day worth saving. The same might be said of Amberlough itself.

2: Fuck respectability.

Amberlough’s characters are diverse, smart, and terribly relatable, but they aren’t anywhere in the vicinity of Good. Aristride is a smuggler and Cordelia is more than happy to help him run his (suffice to say dangerous) wares. Cyril is a liar in and outside of his profession, and I think it’s safe to say that Amberlough’s reputation as a city of vice is well-earned. And yet, it isn’t the virtuous government agent that helps refugees and families broken by the encroaching Ospies, but the smugglers and low-lives. Communities that are built on mutual love and experience are on the frontlines, rather than the heteronormative family units that the Ospies have deemed Good. The author herself put it best when she said, “If the most “respectable” people in society are genocidal fascists, what is respectability worth?”

3: Do the opposite of whatever Cyril would do.

Cyril, of course, is one of the novel’s most respectable characters. Think Ryan Gosling or Gregory Peck in a well-tailored suit: real leading man material. One might be able to tell that I’m not his biggest fan based on my framing of Ari and Cordelia as the novel’s main protagonists above. He is at the center of the story, and makes for a properly frustrating epicenter to all the action. He is also the worst. Brave in his own—if selfish and unsustainable—way, Cyril fights for him and his alone, an act that is as relatable as it is deplorable. He’s a love-to-hate kind of guy, particularly if you (like me) are struggling against your own inclination to hide from the political realities of 2017. But if the communities I mentioned in point 2 are what will save the day, exclusivity and craven self-preservation are hardly the roads to take.

4: Except for loving Aristride.

Cyril’s love for Ari (and, to a lesser extent, for Cordelia) is his most redeeming feature. I could rhapsodize endlessly about the queer representation that Amberlough offers (it’s mature! Complex! And sexy to boot), and could go on even longer about Ari himself (all glam and all performance, and yet the realest of the lot). But more than anything, their relationship is the throughline of a story that is at times bleak and loveless. Despite its notes of tragedy, it is one of the most human and hopeful aspects of the novel.

5: Don’t let them destroy what sustains you.

All this talk of community and love isn’t to say that Amberlough is anywhere in the realm of sentimental. Its characters do fight, and not just for one another, or even for abstract concepts like liberty or freedom. They fight for art: the real protagonist of the story, the life blood of half the cast, the means by which they experience the world. The Bumble Bee Cabaret is the most memorable setting of the novel, and when it comes under threat, readers can’t help but feel the stakes rise. When its performers rise up to protect it, it is an act of self-preservation as much as it is a defense.

6: Know that this isn’t inevitable.

Perhaps the greatest feat of this novel is its simmering, slow build of tension. Fascism is framed in Amberlough as a Lovecraftian monster, creeping and unknowable until the reality of its evil is revealed. However, this pacing and revelation is also the novel’s only real weakness. The slowly-then-all-at-once nature of the Ospies’ ascent to power is brilliantly crafted and very much situated among characters that would treat it as they do—with disregard, selfishness, or scorn, until they’re forced to do otherwise. But by relying on readers to fill in the real-world blanks, the novel at times falls into the trap of presenting xenophobia, misogyny, and homophobia as matters of course, rather than ideologies that are historically situated and not at all ingrained or inevitable. Without projecting real historical ideas and events onto the novel, the reasons behind the Ospies’ social conservatism are unclear.

This doesn’t hurt the novel in any concerted way; I have high hopes that the already-promised sequel to Amberlough is going to address the enemy head-on in a way that the tone of the first novel didn’t quite allow. Oblique references to religious factions, for instance, will inevitably be fleshed out. It’s worth saying, though, in our current political moment: these views, groups like the Ospies, are not inevitable. But they can be fought by the modes of resistance that the novel provides for us.

Amberlough is available from Tor Books.

Read the first four chapters of the novel here on Tor.com.

Emily Nordling is a library assistant and perpetual student in Chicago, IL.